Ask questions about this lesson and get instant answers.

Compound interest is one of the most important concepts in finance. Albert Einstein reportedly called it the "eighth wonder of the world." Whether or not he actually said this, the sentiment is accurate: compound interest can turn modest savings into substantial wealth over time, or turn small debts into overwhelming burdens.

To understand compound interest, we first need to understand simple interest.

Simple interest is interest calculated only on the original amount invested or borrowed. This original amount is called the principal. The interest earned each period remains constant because it is always calculated on the same base.

The formula for simple interest is:

Where:

Let's say you deposit $5,000 into an account that pays 6% simple interest per year, and you leave it there for 4 years.

| Year | Principal | Interest Earned | Balance at Year End |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $5,000 | $300 | $5,300 |

| 2 | $5,000 | $300 | $5,600 |

| 3 | $5,000 | $300 | $5,900 |

| 4 | $5,000 | $300 | $6,200 |

Each year you earn $300 (which is 6% of $5,000). After 4 years, you have earned $1,200 in total interest. Notice that the interest earned is the same every year because simple interest always calculates on the original principal, not on the accumulated balance.

Compound interest is interest calculated on the principal plus any interest already earned. In other words, you earn interest on your interest. This creates a snowball effect where your money grows faster over time.

The formula for compound interest is:

Where:

Using the same example, $5,000 at 6% interest compounded annually for 4 years:

| Year | Starting Balance | Interest Earned | Ending Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $5,000.00 | $300.00 | $5,300.00 |

| 2 | $5,300.00 | $318.00 | $5,618.00 |

| 3 | $5,618.00 | $337.08 | $5,955.08 |

| 4 | $5,955.08 | $357.30 | $6,312.38 |

In Year 1, you earn the same $300 as with simple interest. But in Year 2, you earn 6% on $5,300, not $5,000. That extra $18 might seem small, but notice how it grows each year. By Year 4, you are earning $357.30 in interest, compared to the flat $300 with simple interest.

After 4 years with compound interest, you have $6,312.38 compared to $6,200 with simple interest. That is $112.38 more, earned by doing nothing except letting your interest compound.

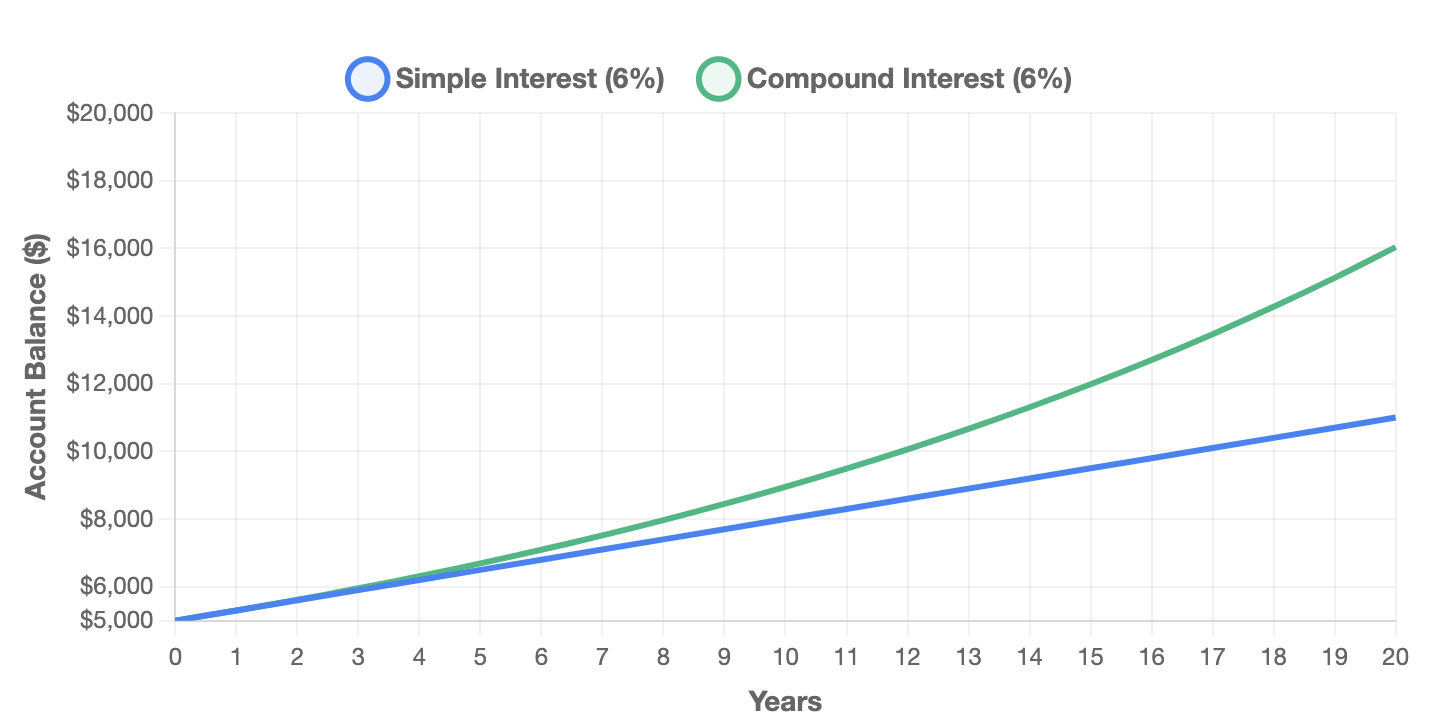

The difference between simple and compound interest becomes dramatic over longer periods. This is because compound interest grows exponentially while simple interest grows linearly.

Let's extend our example to 30 years:

| Time Period | Simple Interest | Compound Interest | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 years | $6,500 | $6,691 | $191 |

| 10 years | $8,000 | $8,954 | $954 |

| 20 years | $11,000 | $16,036 | $5,036 |

| 30 years | $14,000 | $28,717 | $14,717 |

After 30 years, the compound interest account has more than doubled the simple interest account. Your original $5,000 has grown to nearly $29,000, and you earned over $23,000 in interest alone.

This is why starting to save early matters so much. A 25-year-old who invests $5,000 and lets it compound for 40 years will end up with far more than a 45-year-old who invests $10,000 for 20 years, even though the older investor put in twice as much money.

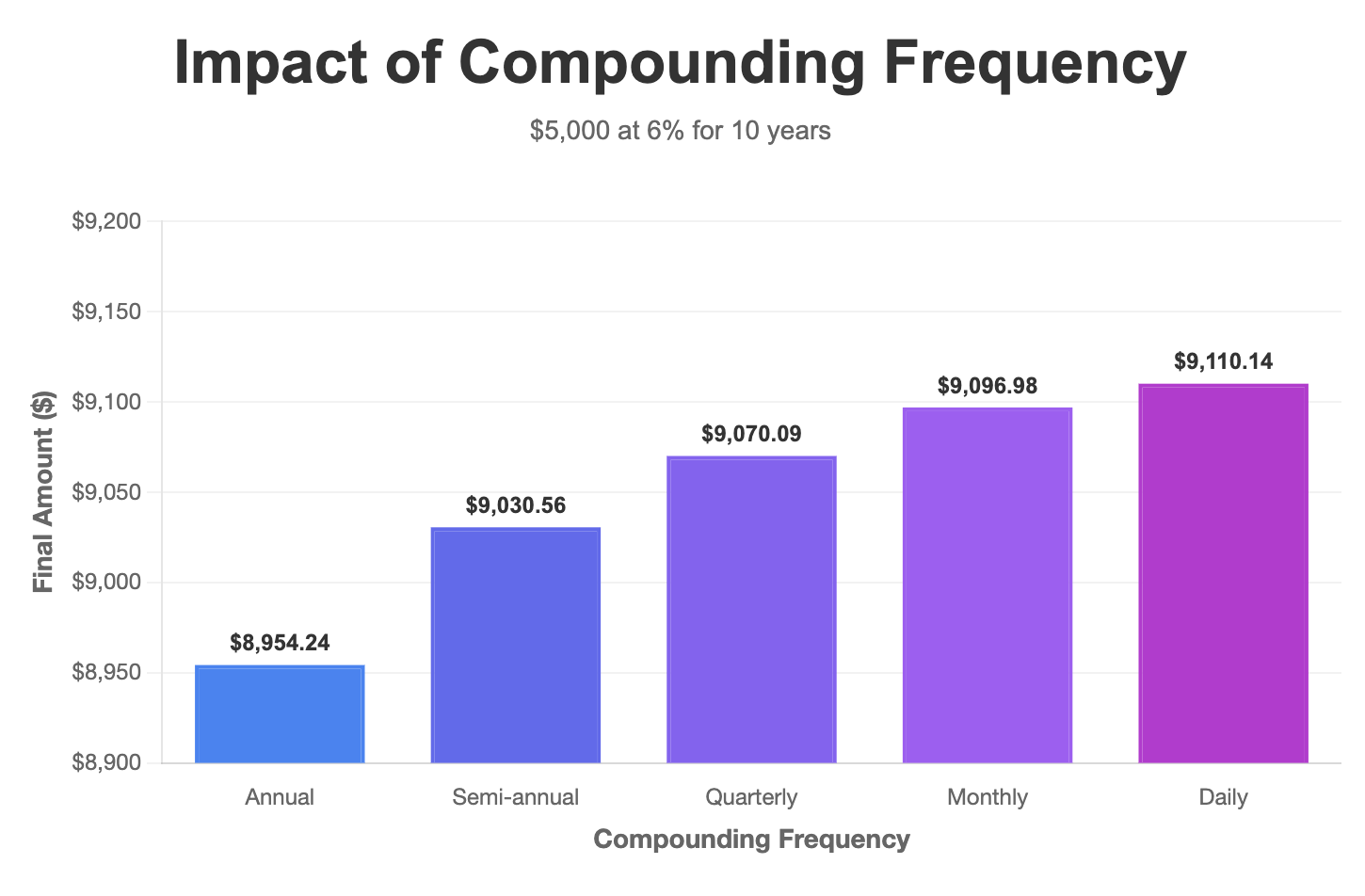

So far we have assumed interest compounds once per year (annually). But interest can compound more frequently: semi-annually (twice per year), quarterly (four times), monthly (twelve times), or even daily.

The more frequently interest compounds, the faster your money grows.

The formula for compound interest with different compounding frequencies is:

Where:

Here is $5,000 at 6% annual interest for 10 years with different compounding frequencies:

| Compounding Frequency | Final Amount | Total Interest Earned |

|---|---|---|

| Annually (1x/year) | $8,954.24 | $3,954.24 |

| Semi-annually (2x/year) | $9,030.56 | $4,030.56 |

| Quarterly (4x/year) | $9,070.09 | $4,070.09 |

| Monthly (12x/year) | $9,096.98 | $4,096.98 |

| Daily (365x/year) | $9,110.14 | $4,110.14 |

The difference between annual and daily compounding over 10 years is about $156. This may not seem like much on $5,000, but on larger amounts and longer time periods, it adds up. This is why banks advertise their APY (Annual Percentage Yield), which accounts for compounding frequency, rather than just the nominal interest rate.

A useful shortcut for estimating compound interest is the Rule of 72. To find how long it takes to double your money, divide 72 by the interest rate.

At 6% interest: 72 ÷ 6 = 12 years to double At 8% interest: 72 ÷ 8 = 9 years to double At 12% interest: 72 ÷ 12 = 6 years to double

This rule is an approximation, but it is remarkably accurate for interest rates between 6% and 10%.

Everything we have discussed applies to debt as well as savings. When you borrow money, compound interest works against you. Credit card debt is particularly dangerous because it compounds on unpaid balances, often at rates of 20% or higher.

At 20% interest compounding monthly, the Rule of 72 tells us debt doubles in about 3.6 years. A $5,000 credit card balance left unpaid would grow to roughly $10,000 in under 4 years, even without any additional purchases.

This is why paying off high-interest debt is often the best "investment" you can make. Eliminating a 20% debt is equivalent to earning a guaranteed 20% return.

Understanding compound interest leads to several practical insights:

Start early. Time is the most important factor in compounding. Starting 10 years earlier can make a bigger difference than doubling your contribution.

Be consistent. Regular contributions combined with compounding create substantial growth. Even small amounts add up when given time to compound.

Mind the rate. Small differences in interest rates matter more than you might think over long periods. A 1% higher return compounded over 30 years makes a significant difference.

Avoid high-interest debt. Compound interest on debt erodes your wealth just as effectively as it builds it on savings. Pay off high-interest debt before focusing on investments.

Compound interest is not magic, but given enough time, it can produce results that feel like it.